How the System Really Works

Global Market Rapport for Organic Fertilizers - 2026 - Trends & Opportunities

Full and free market rapport, Local vs Global Trends, a rapidly growing and fast evolving market with opportunities for distributors, farmers and manufacturers

1. Organic fertilisers: a broad and evolving category

Organic fertilisers are not a single product type.

Globally, they exist in many forms, including:

liquid organic fertilisers

pelletised manure-based products

granular organic and organo-mineral blends

compost and compost-derived inputs

raw and processed animal manures

digestates from biogas installations

insect-derived fertilisers (e.g. frass)

Despite differences in form and processing intensity, organic fertilisers share a common role:

recycling nutrients and organic matter back into food production systems [1][2].

Understanding this diversity is essential when analysing both local initiatives and scalable, export-oriented production.

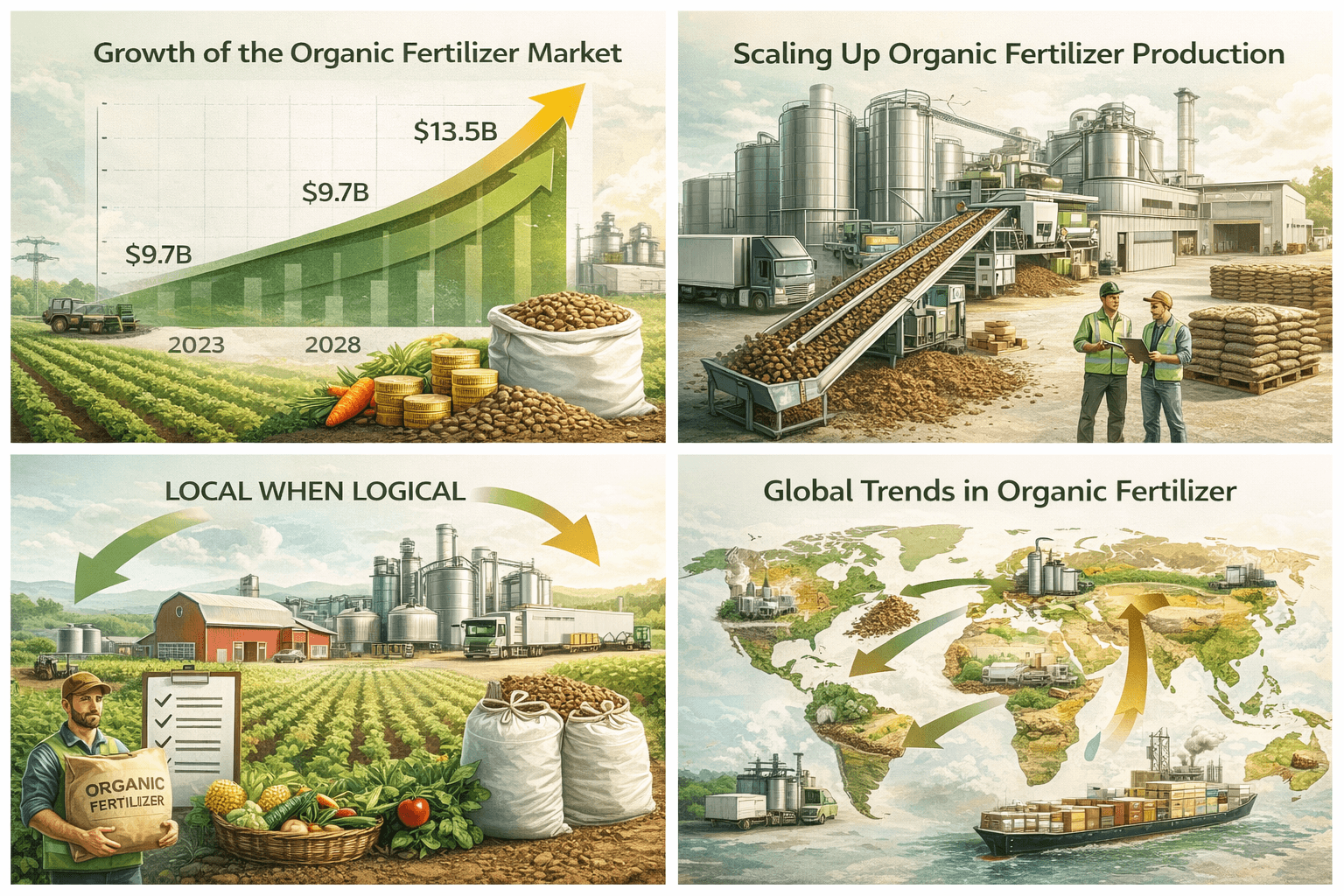

2. Market size and growth: no longer a niche

The global organic fertiliser market is growing steadily and structurally.

Current estimates indicate:

~USD 9.7 billion market size in 2023

projected growth to ~USD 13.5 billion by 2028

representing an average annual growth rate of ~6.5–7% [8][15]

This growth is driven by multiple, reinforcing factors:

expansion of organic and residue-free food production

soil degradation after decades of chemical fertiliser use

regulatory pressure on mineral fertilisers

rising costs and volatility of synthetic inputs

increased focus on soil health and long-term productivity

In specific sub-segments, growth is even faster.

Insect-based fertilisers, for example, are projected to grow at >20–24% CAGR over the coming decade [9].

The market is no longer experimental — it is scaling.

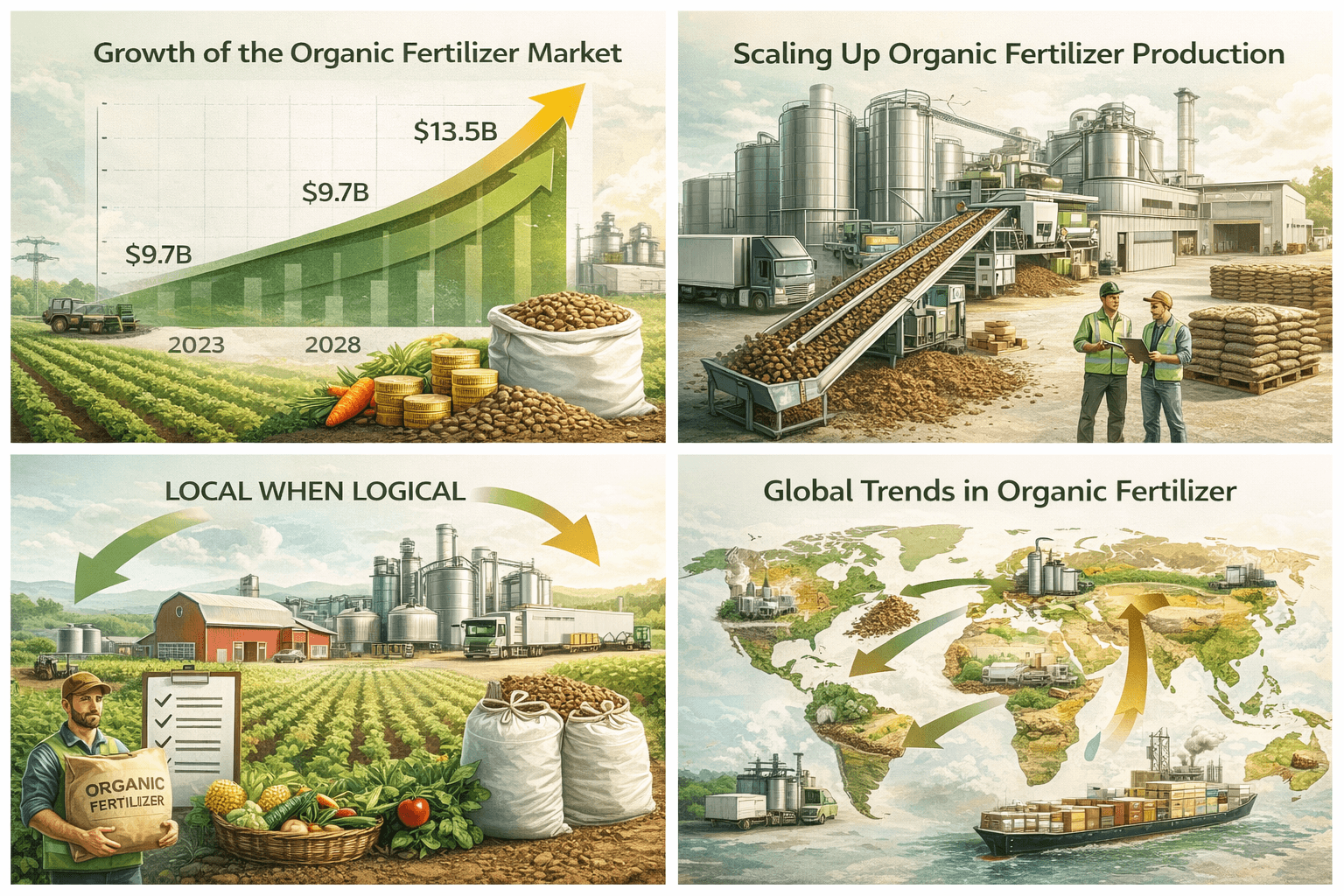

3. Local production is increasing — and it makes sense

Across all continents, local organic fertiliser production is increasing.

This is visible in:

Europe

Latin America

North America

Central America

Africa

Asia

Local initiatives include:

biogas plants valorising digestate

poultry manure pellet processors

composting facilities

insect farming operations

residue-based fertiliser hubs

These developments are driven by:

availability of local organic residues

rising logistics and energy costs

sustainability policies

circular economy incentives

food system self-sufficiency goals [3][4][7][9]

Local production is logical, efficient and often unavoidable.

4. The structural limits of “local only”

However, localisation also has inherent limitations.

Local systems are typically constrained by:

volume tied to regional residue availability

seasonal input streams

variable nutrient composition

limited blending and standardisation

inconsistent supply at scale

As a result:

local products often perform well regionally

but struggle to meet the consistency, volume and reliability required for professional, multi-region distribution

This is not a flaw — it is a structural characteristic of local circular systems [11].

5. Global supply is still driven by livestock-dense regions

Despite the rise of local initiatives, global organic fertiliser volumes are still dominated by countries with high livestock density.

Key producing and exporting countries include:

Netherlands

Italy

Spain

France

United States

China

India

Malaysia

Australia

These countries benefit from:

structural nutrient surpluses

abundant organic raw materials

mature processing infrastructure

export-oriented logistics networks [12][13][14]

Organic fertiliser production in these regions exists primarily because of surplus, not domestic scarcity.

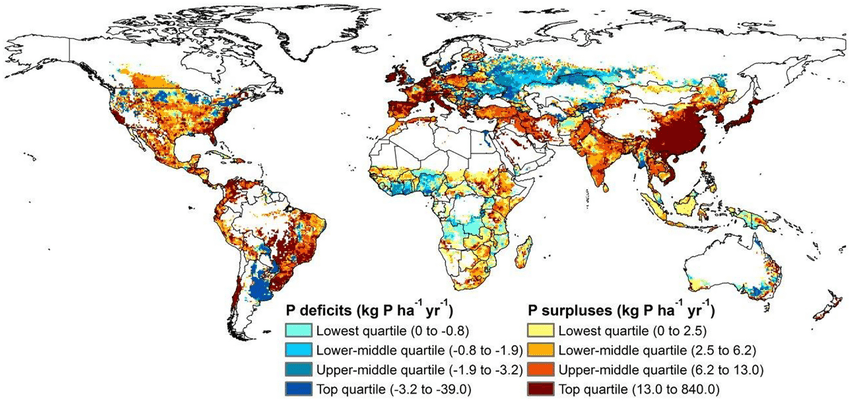

The map below highlights regions with structural Phosporus surpluses (typically livestock-dense areas) and deficit.

This imbalance explains why organic fertilizers are traded internationally: surplus regions will focus on export, while deficit regions rely on imported, concentrated nutrients. Trade flows are driven by nutrient density and logistic costs, rather than borders or ideals of local circularity.

Source: (Bouwman et al., 2017)[19]

6. The Netherlands: a global export hub

The Netherlands is a clear example of this dynamic.

Over 300,000 tonnes of Dutch fertiliser pellets are shipped annually

exports reach more than 75 countries worldwide

export volumes have grown at approximately 15% per year since 2016 [3]

Initially, exports were mainly directed to neighbouring European countries.

Today, a significant share flows to:

Asia

Africa

Latin America [6]

In Southeast Asia, demand is particularly strong due to:

decades of intensive chemical fertiliser use

declining soil organic matter

increasing interest in organic alternatives

Dutch pellets are used as:

soil restorers

organic nutrient sources

blending inputs for local fertiliser production

This illustrates how nutrients move internationally from surplus to deficit regions.

7. Consolidation: major fertiliser players enter organics

With sustained market growth, large fertiliser companies are entering the organic segment.

Examples include:

Yara → Agribios (Italy): expansion into organic inputs and organo-mineral fertilisers [4][10]

EuroChem → Fertilizers with enhanced organic components

Nutrien expanding biological and organic portfolios in North America

ICL investing heavily in bio-based and specialty fertilisers

These players bring:

capital

R&D capacity

regulatory expertise

global distribution networks

This confirms that organic fertilisers are no longer fringe products, but strategic components of future nutrient portfolios [16][17].

8. Farmers buy both local and international — for different reasons

An important shift is happening at farm level.

Farmers increasingly:

source local organic inputs for cost efficiency and circularity

complement them with imported or processed organic fertilisers for consistency, nutrient balance and reliability

Local and international products:

do not compete directly

but fulfil different agronomic and logistical roles

This hybrid sourcing model is becoming the norm.

9. Key global trends shaping the market

9.1 Strong and sustained market growth

Driven by:

organic food demand

soil health awareness

sustainability regulation

pressure on chemical fertilisers [8][11]

9.2 Consolidation and professionalisation

Large fertiliser companies acquire organic specialists to secure future relevance [4][16].

9.3 International nutrient flows

Processed organic fertilisers move from:

livestock-dense regions

tonutrient-depleted agricultural systems [6][12]

9.4 Innovation in sources and technology

insect-based fertilisers

advanced composting

digestate upgrading

concentrated pellets and liquids

precision application tools [9][18]

9.5 Changing perceptions

Organic fertilisers are increasingly valued for:

soil structure improvement

long-term productivity

reduced environmental impact

Chemical fertilisers are gradually losing dominance in some regions due to:

emission concerns

soil degradation

regulatory pressure [11][12]

10. Conclusion

The organic fertiliser market is growing — globally and structurally.

Local production is increasing because it makes sense

Scalable production remains essential for reliability and trade

Farmers increasingly combine both

The future is not local versus global, but local where logical, scalable where necessary.

Understanding that distinction is key for distributors, producers and policymakers alike.

Sources

FAO – Organic Fertilizers and Soil Health

FiBL – The World of Organic Agriculture

Wageningen Economic Research – Manure Processing and Export

New AG International – Yara Acquires Agribios

World Bank – Logistics Costs in Agriculture

FAO – Global Nutrient Flows

European Commission – Circular Economy Action Plan

BCC Research – Global Organic Fertilizer Market

Meticulous Research – Insect Fertilizer Market Forecast

Yara International – Strategic Expansion into Organic Inputs

FAO – Soil Degradation and Nutrient Management

International Fertilizer Association – Organic and Bio-based Fertilizers

USDA – Organic Fertilizer Market Overview

OECD – Agricultural Nutrient Balances

IMARC Group – Organic Fertilizer Market CAGR

Nutrien Investor Reports – Biological and Organic Strategy

ICL Group – Specialty Fertilizers & Bio-based Inputs

IEA Bioenergy – Digestate and Residue Valorisation

Bouwman, A. F., Beusen, A. H. W., Lassaletta, L., van Apeldoorn, D. F., van Grinsven, H. J. M., Zhang, J., & van Ittersum, M. K. (2017). Lessons from temporal and spatial patterns in global use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers on cropland.

1. Organic fertilisers: a broad and evolving category

Organic fertilisers are not a single product type.

Globally, they exist in many forms, including:

liquid organic fertilisers

pelletised manure-based products

granular organic and organo-mineral blends

compost and compost-derived inputs

raw and processed animal manures

digestates from biogas installations

insect-derived fertilisers (e.g. frass)

Despite differences in form and processing intensity, organic fertilisers share a common role:

recycling nutrients and organic matter back into food production systems [1][2].

Understanding this diversity is essential when analysing both local initiatives and scalable, export-oriented production.

2. Market size and growth: no longer a niche

The global organic fertiliser market is growing steadily and structurally.

Current estimates indicate:

~USD 9.7 billion market size in 2023

projected growth to ~USD 13.5 billion by 2028

representing an average annual growth rate of ~6.5–7% [8][15]

This growth is driven by multiple, reinforcing factors:

expansion of organic and residue-free food production

soil degradation after decades of chemical fertiliser use

regulatory pressure on mineral fertilisers

rising costs and volatility of synthetic inputs

increased focus on soil health and long-term productivity

In specific sub-segments, growth is even faster.

Insect-based fertilisers, for example, are projected to grow at >20–24% CAGR over the coming decade [9].

The market is no longer experimental — it is scaling.

3. Local production is increasing — and it makes sense

Across all continents, local organic fertiliser production is increasing.

This is visible in:

Europe

Latin America

North America

Central America

Africa

Asia

Local initiatives include:

biogas plants valorising digestate

poultry manure pellet processors

composting facilities

insect farming operations

residue-based fertiliser hubs

These developments are driven by:

availability of local organic residues

rising logistics and energy costs

sustainability policies

circular economy incentives

food system self-sufficiency goals [3][4][7][9]

Local production is logical, efficient and often unavoidable.

4. The structural limits of “local only”

However, localisation also has inherent limitations.

Local systems are typically constrained by:

volume tied to regional residue availability

seasonal input streams

variable nutrient composition

limited blending and standardisation

inconsistent supply at scale

As a result:

local products often perform well regionally

but struggle to meet the consistency, volume and reliability required for professional, multi-region distribution

This is not a flaw — it is a structural characteristic of local circular systems [11].

5. Global supply is still driven by livestock-dense regions

Despite the rise of local initiatives, global organic fertiliser volumes are still dominated by countries with high livestock density.

Key producing and exporting countries include:

Netherlands

Italy

Spain

France

United States

China

India

Malaysia

Australia

These countries benefit from:

structural nutrient surpluses

abundant organic raw materials

mature processing infrastructure

export-oriented logistics networks [12][13][14]

Organic fertiliser production in these regions exists primarily because of surplus, not domestic scarcity.

The map below highlights regions with structural Phosporus surpluses (typically livestock-dense areas) and deficit.

This imbalance explains why organic fertilizers are traded internationally: surplus regions will focus on export, while deficit regions rely on imported, concentrated nutrients. Trade flows are driven by nutrient density and logistic costs, rather than borders or ideals of local circularity.

Source: (Bouwman et al., 2017)[19]

6. The Netherlands: a global export hub

The Netherlands is a clear example of this dynamic.

Over 300,000 tonnes of Dutch fertiliser pellets are shipped annually

exports reach more than 75 countries worldwide

export volumes have grown at approximately 15% per year since 2016 [3]

Initially, exports were mainly directed to neighbouring European countries.

Today, a significant share flows to:

Asia

Africa

Latin America [6]

In Southeast Asia, demand is particularly strong due to:

decades of intensive chemical fertiliser use

declining soil organic matter

increasing interest in organic alternatives

Dutch pellets are used as:

soil restorers

organic nutrient sources

blending inputs for local fertiliser production

This illustrates how nutrients move internationally from surplus to deficit regions.

7. Consolidation: major fertiliser players enter organics

With sustained market growth, large fertiliser companies are entering the organic segment.

Examples include:

Yara → Agribios (Italy): expansion into organic inputs and organo-mineral fertilisers [4][10]

EuroChem → Fertilizers with enhanced organic components

Nutrien expanding biological and organic portfolios in North America

ICL investing heavily in bio-based and specialty fertilisers

These players bring:

capital

R&D capacity

regulatory expertise

global distribution networks

This confirms that organic fertilisers are no longer fringe products, but strategic components of future nutrient portfolios [16][17].

8. Farmers buy both local and international — for different reasons

An important shift is happening at farm level.

Farmers increasingly:

source local organic inputs for cost efficiency and circularity

complement them with imported or processed organic fertilisers for consistency, nutrient balance and reliability

Local and international products:

do not compete directly

but fulfil different agronomic and logistical roles

This hybrid sourcing model is becoming the norm.

9. Key global trends shaping the market

9.1 Strong and sustained market growth

Driven by:

organic food demand

soil health awareness

sustainability regulation

pressure on chemical fertilisers [8][11]

9.2 Consolidation and professionalisation

Large fertiliser companies acquire organic specialists to secure future relevance [4][16].

9.3 International nutrient flows

Processed organic fertilisers move from:

livestock-dense regions

tonutrient-depleted agricultural systems [6][12]

9.4 Innovation in sources and technology

insect-based fertilisers

advanced composting

digestate upgrading

concentrated pellets and liquids

precision application tools [9][18]

9.5 Changing perceptions

Organic fertilisers are increasingly valued for:

soil structure improvement

long-term productivity

reduced environmental impact

Chemical fertilisers are gradually losing dominance in some regions due to:

emission concerns

soil degradation

regulatory pressure [11][12]

10. Conclusion

The organic fertiliser market is growing — globally and structurally.

Local production is increasing because it makes sense

Scalable production remains essential for reliability and trade

Farmers increasingly combine both

The future is not local versus global, but local where logical, scalable where necessary.

Understanding that distinction is key for distributors, producers and policymakers alike.

Sources

FAO – Organic Fertilizers and Soil Health

FiBL – The World of Organic Agriculture

Wageningen Economic Research – Manure Processing and Export

New AG International – Yara Acquires Agribios

World Bank – Logistics Costs in Agriculture

FAO – Global Nutrient Flows

European Commission – Circular Economy Action Plan

BCC Research – Global Organic Fertilizer Market

Meticulous Research – Insect Fertilizer Market Forecast

Yara International – Strategic Expansion into Organic Inputs

FAO – Soil Degradation and Nutrient Management

International Fertilizer Association – Organic and Bio-based Fertilizers

USDA – Organic Fertilizer Market Overview

OECD – Agricultural Nutrient Balances

IMARC Group – Organic Fertilizer Market CAGR

Nutrien Investor Reports – Biological and Organic Strategy

ICL Group – Specialty Fertilizers & Bio-based Inputs

IEA Bioenergy – Digestate and Residue Valorisation

Bouwman, A. F., Beusen, A. H. W., Lassaletta, L., van Apeldoorn, D. F., van Grinsven, H. J. M., Zhang, J., & van Ittersum, M. K. (2017). Lessons from temporal and spatial patterns in global use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers on cropland.

Related posts