Context & Markets

Why we don't sell organic fertilizers in The Netherlands

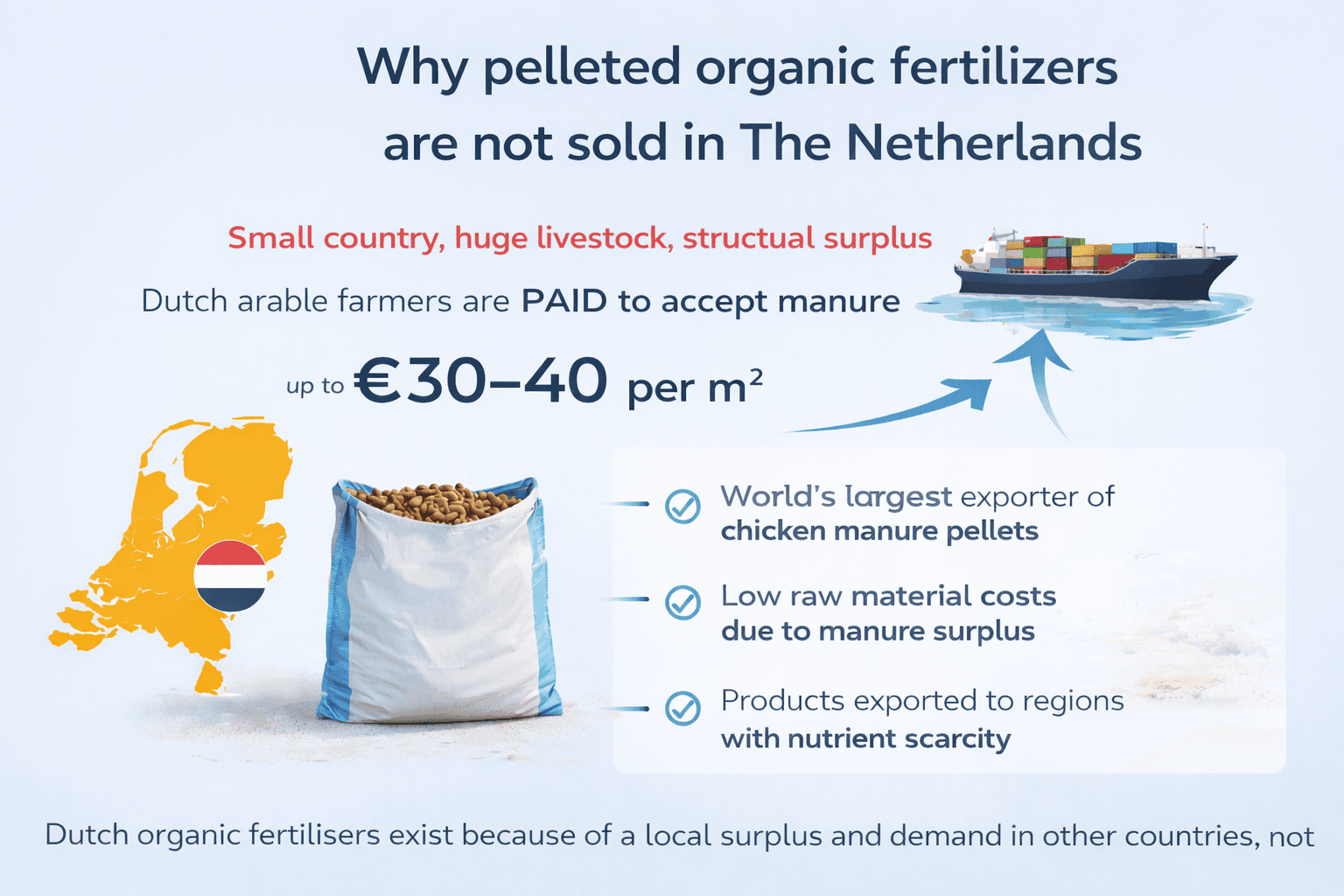

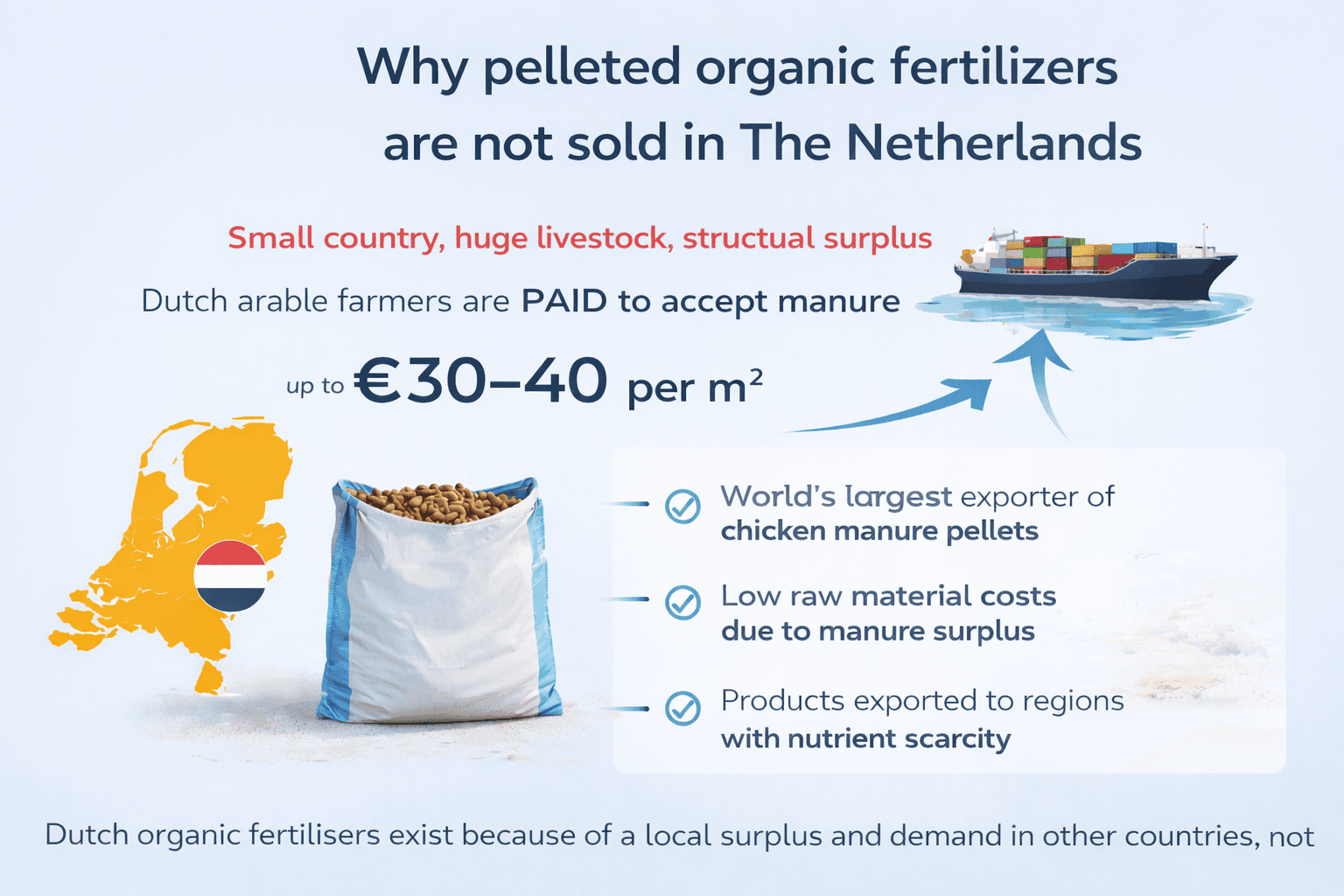

The Netherlands is a very small country with an exceptionally high livestock density. As a result: animal manure production far exceeds land capacity nutrient application is constrained by regulation, not by crop demand manure handling is primarily a disposal and logistics issue

Why next-generation organic fertilisers like ours don’t make sense in the Netherlands

This may sound counterintuitive coming from a company that develops next-generation organic fertilisers.

But it needs to be said clearly:

Our fertilisers are usually not very relevant for Dutch agriculture.

Not because they don’t work.

But because they don’t solve a real problem here.

The Dutch reality: manure is not scarce — it’s excessive

The Netherlands is a very small country with an exceptionally high livestock density.

As a result:

manure production exceeds land capacity

nutrient use is limited by regulation, not crop demand

manure handling is mainly a disposal and logistics issue

This leads to a situation that surprises many people outside the Netherlands:

Arable farmers are often paid to accept manure.

In practice:

manure is delivered at very low cost

or with a gate fee paid to the farmer

in some regions up to €30–40 per m³

That single fact defines the market.

When farmers are paid to take nutrients, adding more rarely helps

In large parts of Dutch arable farming:

nitrogen is not limiting

phosphorus is not limiting

organic matter inputs are already high

Farmers are constrained by:

application ceilings

timing rules

emission limits

Not by a lack of nutrients.

In this context, adding another organic fertiliser:

does not improve nutrient efficiency

does not improve farm economics

does not address the main bottlenecks

It simply adds volume to an already saturated system.

Manure surplus drives export and not domestic demand

Ironically, the same surplus that limits relevance at home

is why the Netherlands plays such a dominant role internationally.

Despite its size, the Netherlands is by far the largest exporter of chicken manure pellets worldwide.

Not because Dutch soils need them — but because other regions do.

The surplus leads to:

low domestic manure prices

abundant organic raw materials

large-scale processing capacity

a strongly export-oriented fertiliser industry

Many Dutch organic and organo-mineral fertilisers are designed from the start for markets where:

nutrients are scarce

soils are depleted

organic inputs are limited

mineral fertilisers dominate

In short:

Dutch organic fertilisers exist because of surplus, not because Dutch agriculture lacks nutrients.

“But organic matter is always good, right?”

Organic matter is valuable.

But context matters.

In many Dutch systems:

soil organic matter levels are already relatively high

crop residues are returned

manure applications are routine

Additional organic inputs often result in:

diminishing returns

limited yield response

no clear economic benefit

Organic or biological does not automatically mean:

necessary

logical

effective

Especially not in a system defined by oversupply.

Why we say this — even though we are based in the Netherlands

We are based in the Netherlands.

We work with Dutch raw materials.

We operate inside this system.

That is exactly why we are explicit about its limits.

Our next-generation fertilisers are developed to solve problems related to:

nutrient scarcity

depleted soils

lack of organic inputs

overreliance on mineral fertilisers

Those problems simply do not define mainstream Dutch agriculture.

Pretending otherwise would be misleading.

Conclusion

Next-generation organic fertilisers work best where nutrients and organic matter are scarce.

The Netherlands has the opposite problem: structural surplus.

That is why:

manure is cheap

farmers are paid to accept it

organic fertilisers are exported at scale

Including by us.

Good products are context-dependent.

Ignoring that doesn’t help farmers — it confuses them.

Why next-generation organic fertilisers like ours don’t make sense in the Netherlands

This may sound counterintuitive coming from a company that develops next-generation organic fertilisers.

But it needs to be said clearly:

Our fertilisers are usually not very relevant for Dutch agriculture.

Not because they don’t work.

But because they don’t solve a real problem here.

The Dutch reality: manure is not scarce — it’s excessive

The Netherlands is a very small country with an exceptionally high livestock density.

As a result:

manure production exceeds land capacity

nutrient use is limited by regulation, not crop demand

manure handling is mainly a disposal and logistics issue

This leads to a situation that surprises many people outside the Netherlands:

Arable farmers are often paid to accept manure.

In practice:

manure is delivered at very low cost

or with a gate fee paid to the farmer

in some regions up to €30–40 per m³

That single fact defines the market.

When farmers are paid to take nutrients, adding more rarely helps

In large parts of Dutch arable farming:

nitrogen is not limiting

phosphorus is not limiting

organic matter inputs are already high

Farmers are constrained by:

application ceilings

timing rules

emission limits

Not by a lack of nutrients.

In this context, adding another organic fertiliser:

does not improve nutrient efficiency

does not improve farm economics

does not address the main bottlenecks

It simply adds volume to an already saturated system.

Manure surplus drives export and not domestic demand

Ironically, the same surplus that limits relevance at home

is why the Netherlands plays such a dominant role internationally.

Despite its size, the Netherlands is by far the largest exporter of chicken manure pellets worldwide.

Not because Dutch soils need them — but because other regions do.

The surplus leads to:

low domestic manure prices

abundant organic raw materials

large-scale processing capacity

a strongly export-oriented fertiliser industry

Many Dutch organic and organo-mineral fertilisers are designed from the start for markets where:

nutrients are scarce

soils are depleted

organic inputs are limited

mineral fertilisers dominate

In short:

Dutch organic fertilisers exist because of surplus, not because Dutch agriculture lacks nutrients.

“But organic matter is always good, right?”

Organic matter is valuable.

But context matters.

In many Dutch systems:

soil organic matter levels are already relatively high

crop residues are returned

manure applications are routine

Additional organic inputs often result in:

diminishing returns

limited yield response

no clear economic benefit

Organic or biological does not automatically mean:

necessary

logical

effective

Especially not in a system defined by oversupply.

Why we say this — even though we are based in the Netherlands

We are based in the Netherlands.

We work with Dutch raw materials.

We operate inside this system.

That is exactly why we are explicit about its limits.

Our next-generation fertilisers are developed to solve problems related to:

nutrient scarcity

depleted soils

lack of organic inputs

overreliance on mineral fertilisers

Those problems simply do not define mainstream Dutch agriculture.

Pretending otherwise would be misleading.

Conclusion

Next-generation organic fertilisers work best where nutrients and organic matter are scarce.

The Netherlands has the opposite problem: structural surplus.

That is why:

manure is cheap

farmers are paid to accept it

organic fertilisers are exported at scale

Including by us.

Good products are context-dependent.

Ignoring that doesn’t help farmers — it confuses them.

Related posts