Agronomy, Without the Myths

Chloride in fertilisers: context matters more than content

Chloride problems in agriculture are often blamed on fertilisers. This article explains why organic fertilisers are rarely the real issue — and why water, mineral inputs and total chloride load matter far more

Chloride in organic fertilisers

Why it is rarely the real problem

Let’s start with something familiar.

Plants are a bit like people:

they need a small amount of salt to function properly.

Too little, and basic processes slow down.

Too much, and problems appear quickly.

So yes — chloride matters.

But the real issue is not its presence, it’s its accumulation.

That distinction is often lost.

This article explains why.

First things first: what is chloride?

Chloride (Cl⁻) is:

a negatively charged ion

fully water-soluble

hardly bound to soil particles

present mainly in soil water, not in the solid soil phase

From an agronomic perspective, chloride:

does not build soil structure

is rarely applied intentionally as a nutrient

behaves largely as a passenger, moving wherever water moves

Or more simply:

Plants don’t “see” fertilisers.

They respond to ion concentrations in the root zone.

This is fundamental to understanding chloride behaviour.

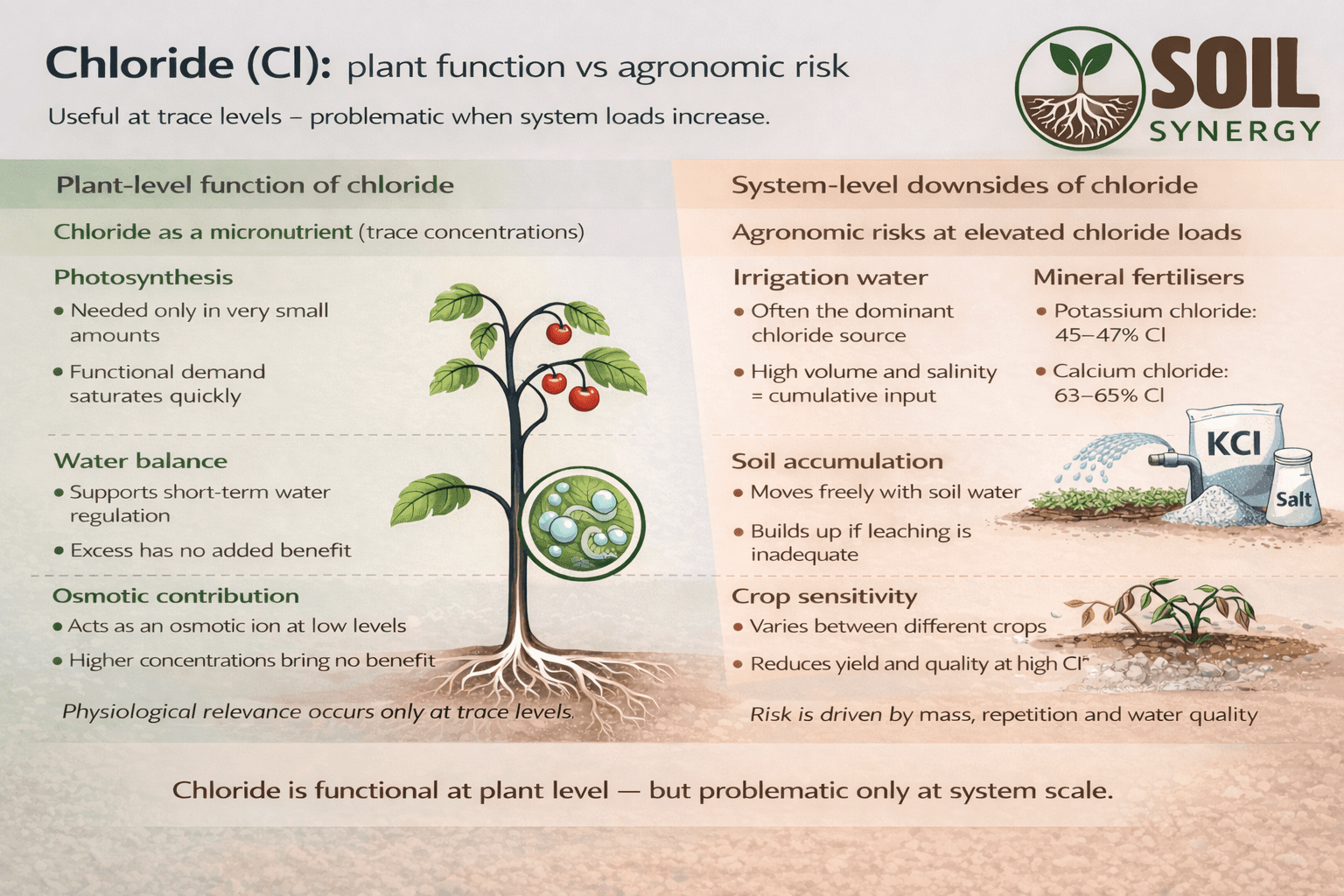

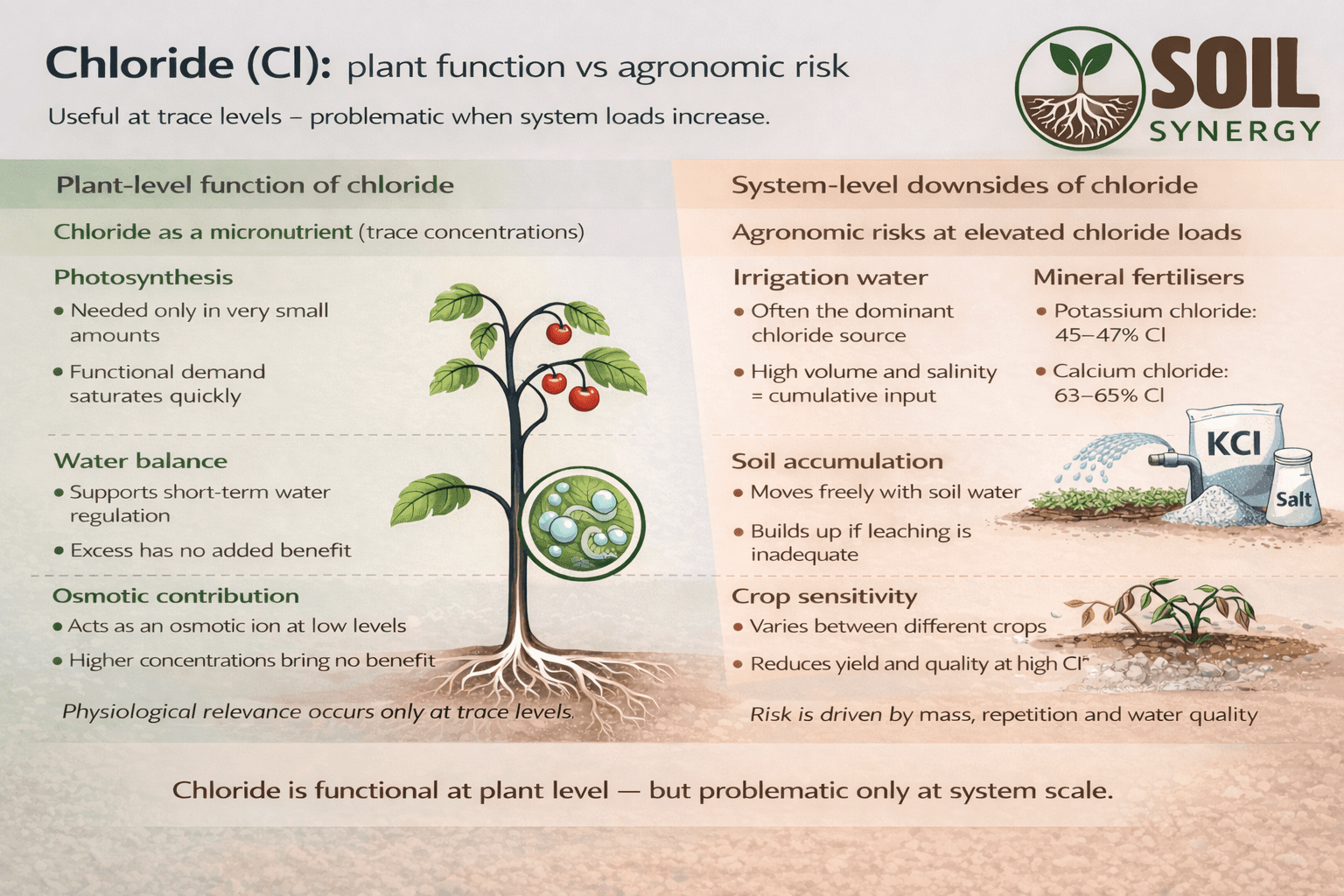

Chloride at plant level: useful, but only in traces

Chloride is officially classified as an essential micronutrient.

At very low concentrations, plants actively use chloride as part of their physiological machinery. Research shows that chloride contributes to:

normal photosynthetic functioning

osmotic regulation at cellular level

maintaining ionic balance alongside potassium and calcium

Chloride deficiency can occur, but under practical field conditions it is rare.

Where it does appear, reported symptoms include:

wilting despite sufficient water

chlorosis and reduced leaf expansion

excessive lateral root branching

These symptoms are often mistaken for nitrogen or potassium deficiencies, which makes correct diagnosis important.

The key point:

The physiological demand for chloride is extremely small and saturates quickly.

Beyond trace levels, additional chloride does not improve plant function.

When chloride becomes a problem

Most chloride-related issues are not biological, but systemic.

At elevated system loads, chloride can:

accumulate in the root zone

interfere with nitrate uptake

reduce yield and quality

cause leaf tip burn and marginal necrosis

Chloride toxicity is far more common than deficiency, especially in systems with saline irrigation water or repeated chloride inputs.

Crop sensitivity also matters:

Chloride-sensitive crops include beans, berries, grapes, potatoes and many greenhouse crops

More tolerant crops include barley, sugar beet and some forage grasses

Chloride management is therefore crop-specific, not ideological.

The real question you should ask

Not:

“Does my fertiliser contain chloride?”

But:

“How much chloride enters my system in total?”

This is where many discussions go wrong.

How much chloride comes from where?

Let’s look at order of magnitude, not labels.

Indicative chloride inputs in agriculture

Source | Chloride (Cl) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

Organic fertiliser (poultry manure pellets) | 0.2–0.7 % | Highly variable |

Next-generation organic fertiliser | ~0.75 % | Slightly higher, same order |

Potassium chloride (KCl / MOP) | ~45–47 % | Very high chloride input |

Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) | ~63–65 % | Extremely concentrated |

Rainwater | <10 mg/L | Practically chloride-free |

Fresh irrigation water | 20–150 mg/L | Often underestimated |

Brackish irrigation water | 200–1,000+ mg/L | Where problems start |

Putting this into perspective

The difference between:

0.5 % chloride

and 0.75 % chloride

in an organic fertiliser is negligible compared to:

repeated use of KCl-based fertilisers

years of chloride-containing NPK applications

large volumes of irrigation water

Or put differently:

If your system already receives hundreds of kilograms of chloride per hectare per year from water or mineral fertilisers,

a few extra kilograms from organic fertiliser will not make or break the system.

Water: the silent chloride contributor

This factor is frequently underestimated.

A simple calculation:

5,000 m³ irrigation water per hectare

× 200 mg chloride per litre (moderately brackish)

= 1,000 kg chloride per hectare per year

That is:

far more than organic fertilisers contribute

often more than fertilisers combined

Chloride is mobile, which means it can be leached — but only under the right conditions.

Leaching works when:

drainage is sufficient

irrigation water itself is low in chloride

Leaching saline soils with saline water

is not leaching — it’s redistribution.

“But organic fertilisers help desalination, right?”

Indirectly — yes.

But with clear limits.

Organic matter can:

improve soil structure

increase infiltration

enhance water movement through the soil profile

This improves the system’s capacity to flush salts out — if water quality allows it.

But:

Organic fertilisers do not remove chloride.

They only enable removal under the right conditions.

No clean water = no real desalination.

Practical chloride management: what actually helps

Effective chloride management focuses on system controls, not individual products:

Water quality first

Irrigation water largely determines the chloride ceiling of a system.Mineral fertiliser source selection

Sulphate- or nitrate-based potassium sources matter far more than minor chloride differences in organic inputs.Soil monitoring

Chloride must be interpreted in relation to texture, drainage and irrigation history.Organic matter as an enabler, not a solution

Organic inputs improve structure and infiltration but do not neutralise chloride.

Why chloride in organic fertilisers is rarely decisive

Even if:

a next-generation organic fertiliser

contains slightly more chloride

than conventional poultry manure pellets

the reality remains:

absolute chloride input is small

application rates are limited

system impact is marginal

Chloride issues are driven by:

volume

repetition

water quality

Not by one organic product.

Conclusion

Chloride is everywhere.

The real question is not whether chloride is present,

but whether it accumulates to levels that harm soil and crops.

Focusing on the chloride content of a single fertiliser

while ignoring:

irrigation water

fertiliser history

total chloride load

means missing the real drivers.

Organic fertilisers can fit perfectly well into a sound system.

But the idea that “a bit of chloride in organic fertiliser” is decisive

simply doesn’t hold up.

Chloride itself is not the enemy.

Poor system design is.

Sources

FAO – Water Quality for Agriculture (Ayers & Westcot)

FAO – *Salt-affected soils and their management

Havlin et al. - Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: An Introduction to Nutrient Management

Ayers, R.S. & Westcot, D.W. (FAO) - Water Quality for Agriculture -FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 29

Chloride in organic fertilisers

Why it is rarely the real problem

Let’s start with something familiar.

Plants are a bit like people:

they need a small amount of salt to function properly.

Too little, and basic processes slow down.

Too much, and problems appear quickly.

So yes — chloride matters.

But the real issue is not its presence, it’s its accumulation.

That distinction is often lost.

This article explains why.

First things first: what is chloride?

Chloride (Cl⁻) is:

a negatively charged ion

fully water-soluble

hardly bound to soil particles

present mainly in soil water, not in the solid soil phase

From an agronomic perspective, chloride:

does not build soil structure

is rarely applied intentionally as a nutrient

behaves largely as a passenger, moving wherever water moves

Or more simply:

Plants don’t “see” fertilisers.

They respond to ion concentrations in the root zone.

This is fundamental to understanding chloride behaviour.

Chloride at plant level: useful, but only in traces

Chloride is officially classified as an essential micronutrient.

At very low concentrations, plants actively use chloride as part of their physiological machinery. Research shows that chloride contributes to:

normal photosynthetic functioning

osmotic regulation at cellular level

maintaining ionic balance alongside potassium and calcium

Chloride deficiency can occur, but under practical field conditions it is rare.

Where it does appear, reported symptoms include:

wilting despite sufficient water

chlorosis and reduced leaf expansion

excessive lateral root branching

These symptoms are often mistaken for nitrogen or potassium deficiencies, which makes correct diagnosis important.

The key point:

The physiological demand for chloride is extremely small and saturates quickly.

Beyond trace levels, additional chloride does not improve plant function.

When chloride becomes a problem

Most chloride-related issues are not biological, but systemic.

At elevated system loads, chloride can:

accumulate in the root zone

interfere with nitrate uptake

reduce yield and quality

cause leaf tip burn and marginal necrosis

Chloride toxicity is far more common than deficiency, especially in systems with saline irrigation water or repeated chloride inputs.

Crop sensitivity also matters:

Chloride-sensitive crops include beans, berries, grapes, potatoes and many greenhouse crops

More tolerant crops include barley, sugar beet and some forage grasses

Chloride management is therefore crop-specific, not ideological.

The real question you should ask

Not:

“Does my fertiliser contain chloride?”

But:

“How much chloride enters my system in total?”

This is where many discussions go wrong.

How much chloride comes from where?

Let’s look at order of magnitude, not labels.

Indicative chloride inputs in agriculture

Source | Chloride (Cl) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

Organic fertiliser (poultry manure pellets) | 0.2–0.7 % | Highly variable |

Next-generation organic fertiliser | ~0.75 % | Slightly higher, same order |

Potassium chloride (KCl / MOP) | ~45–47 % | Very high chloride input |

Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) | ~63–65 % | Extremely concentrated |

Rainwater | <10 mg/L | Practically chloride-free |

Fresh irrigation water | 20–150 mg/L | Often underestimated |

Brackish irrigation water | 200–1,000+ mg/L | Where problems start |

Putting this into perspective

The difference between:

0.5 % chloride

and 0.75 % chloride

in an organic fertiliser is negligible compared to:

repeated use of KCl-based fertilisers

years of chloride-containing NPK applications

large volumes of irrigation water

Or put differently:

If your system already receives hundreds of kilograms of chloride per hectare per year from water or mineral fertilisers,

a few extra kilograms from organic fertiliser will not make or break the system.

Water: the silent chloride contributor

This factor is frequently underestimated.

A simple calculation:

5,000 m³ irrigation water per hectare

× 200 mg chloride per litre (moderately brackish)

= 1,000 kg chloride per hectare per year

That is:

far more than organic fertilisers contribute

often more than fertilisers combined

Chloride is mobile, which means it can be leached — but only under the right conditions.

Leaching works when:

drainage is sufficient

irrigation water itself is low in chloride

Leaching saline soils with saline water

is not leaching — it’s redistribution.

“But organic fertilisers help desalination, right?”

Indirectly — yes.

But with clear limits.

Organic matter can:

improve soil structure

increase infiltration

enhance water movement through the soil profile

This improves the system’s capacity to flush salts out — if water quality allows it.

But:

Organic fertilisers do not remove chloride.

They only enable removal under the right conditions.

No clean water = no real desalination.

Practical chloride management: what actually helps

Effective chloride management focuses on system controls, not individual products:

Water quality first

Irrigation water largely determines the chloride ceiling of a system.Mineral fertiliser source selection

Sulphate- or nitrate-based potassium sources matter far more than minor chloride differences in organic inputs.Soil monitoring

Chloride must be interpreted in relation to texture, drainage and irrigation history.Organic matter as an enabler, not a solution

Organic inputs improve structure and infiltration but do not neutralise chloride.

Why chloride in organic fertilisers is rarely decisive

Even if:

a next-generation organic fertiliser

contains slightly more chloride

than conventional poultry manure pellets

the reality remains:

absolute chloride input is small

application rates are limited

system impact is marginal

Chloride issues are driven by:

volume

repetition

water quality

Not by one organic product.

Conclusion

Chloride is everywhere.

The real question is not whether chloride is present,

but whether it accumulates to levels that harm soil and crops.

Focusing on the chloride content of a single fertiliser

while ignoring:

irrigation water

fertiliser history

total chloride load

means missing the real drivers.

Organic fertilisers can fit perfectly well into a sound system.

But the idea that “a bit of chloride in organic fertiliser” is decisive

simply doesn’t hold up.

Chloride itself is not the enemy.

Poor system design is.

Sources

FAO – Water Quality for Agriculture (Ayers & Westcot)

FAO – *Salt-affected soils and their management

Havlin et al. - Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: An Introduction to Nutrient Management

Ayers, R.S. & Westcot, D.W. (FAO) - Water Quality for Agriculture -FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 29

Related posts